UT Professor Shines Light on Virginia Woolf

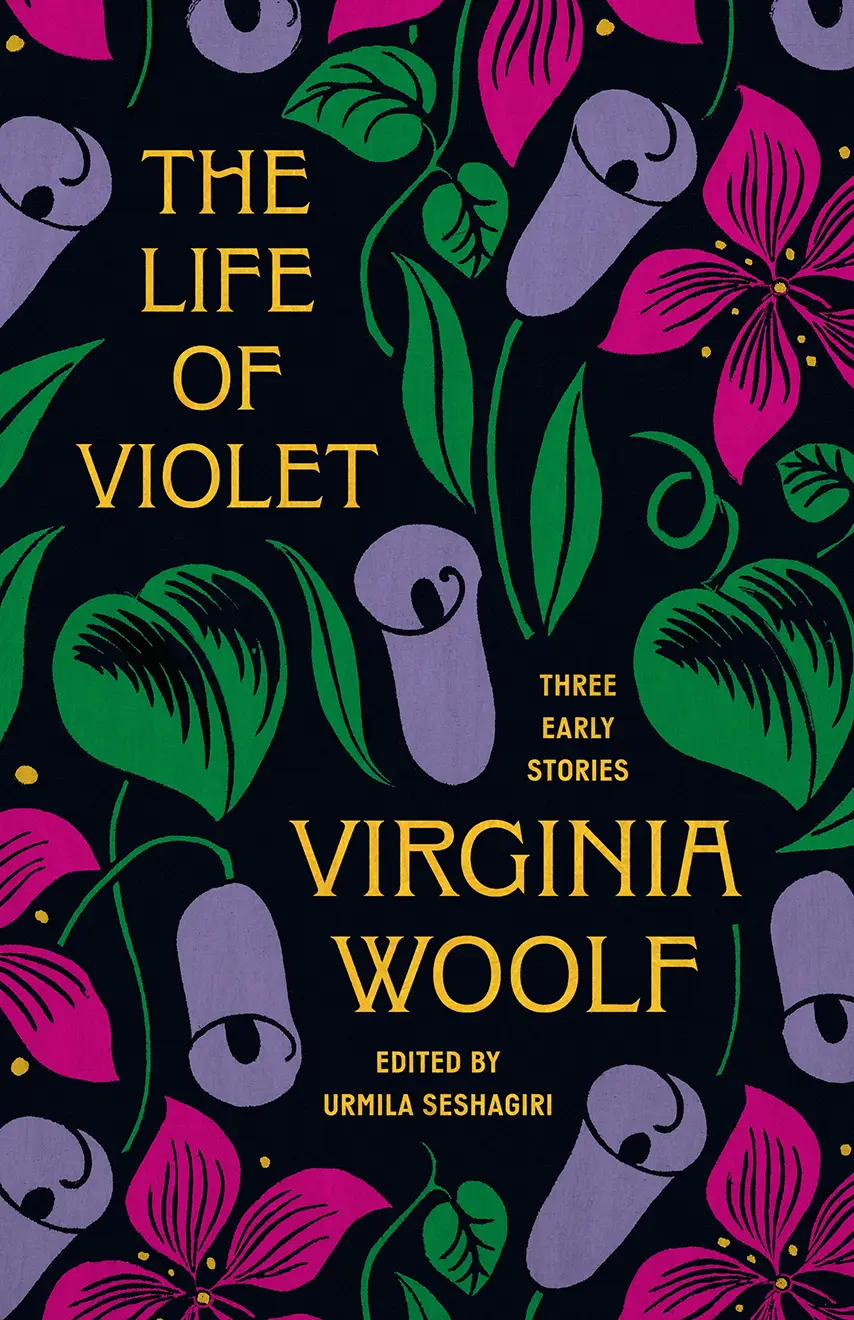

UT Professor Urmila Seshagiri’s scholarship provides context for Virginia Woolf’s first fully realized work of fiction in The Life of Violet: Three Early Stories.

A century after Virginia Woolf became a leading modernist writer, a professor from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, is showing the world a new side of her, through three of the author’s previously unpublished comic stories.

“People find Woolf intimidating—her novels like Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse might feel difficult, complicated— but these stories welcome the reader in immediately, and above all, they make you laugh,” said Urmila Seshagiri, Distinguished Professor in Humanities.

The Life of Violet: Three Early Stories is a mock-biography that Woolf wrote for her friend Mary Violet Dickinson in 1907, featuring a giantess named Violet who rejects the social traditions of the time.

“Violet was 6 feet, 2 inches tall, an astonishing and inconvenient height for a woman born in Victorian England,” Seshagiri explained. “She was one of Woolf’s closest friends as well as a mentor at the early stage of her writing career, and Woolf concocted three short stories filled with inside jokes, parodies of people in their social circle, and all sorts of magical and absurd happenings.”

The newly published volume Seshagiri edited—incorporating Woolf’s handwritten changes on a professionally typed manuscript—shows these were not just lighthearted tales Woolf wrote for friends and family but her first fully realized literary experiment.

Seshagiri served as editor of a new edition of Woolf’s groundbreaking novel Jacob’s Room, which was first published in 1922, and hopes to finalize the first scholarly edition of Woolf’s memoir, Sketch of the Past, in 2026.

The Moment of Discovery

While researching Woolf’s papers at the University of Sussex in 2018, the professor learned there was a typewritten manuscript of the Violet stories. However, she initially thought it would be just a copy of an early draft in the New York Public Library.

Because of the pandemic, copyright laws, and other complications, Seshagiri was unable to see the document until October 2022, when she was invited to the Longleat House estate, where Dickinson’s papers are housed. There, the archivist gave her a document box with a bound typescript.

“When I turned to the first page, my heart leaped because I saw that it was, in fact, a revision of stories we had thought to exist only in draft form,” she said. “I saw how elegantly Woolf had revised her first drafts, and I realized I was reading pages that scholars and Woolf readers had never seen.”

Seshagiri’s discovery also led to new opportunities for students working with her at the time, graduate research assistant Kathryn Bradshaw and undergraduate Izzy Alexander (’25), who is now pursuing a master’s degree in English at UT.

“These students came to see what was involved with archival work: the way sometimes tedious hours in a library can suddenly, unexpectedly turn into moments that alter your perspective,” she said.

“They helped to check my transcription and learned what was involved in writing annotations, which sound like humdrum tasks but are actually very exciting,” Seshagiri said. “Each step involves asking the questions that are foundational to university education: What do we know? What can, or should, we know? And how can we transmit this knowledge to other people?”

Seshagiri’s afterword provides historical, biographical, and literary context for the work Woolf wrote nearly a decade before her first novel was published.

The discovery and Seshagiri’s book are already generating excitement. She has been interviewed by the BBC and The Sunday Times in the United Kingdom, as well as The Washington Post.

By Amy Beth Miller