Hendrix’s Poetry Book Featured in State Series

During fall break, Lecturer Raye Hendrix in the Department of English served as a visiting artist at another university, reading from and discussing their first book of poetry.

Hendrix, who joined the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, this year, was named the 2024 Lynne Burris Butler Visiting Artist for the University of North Alabama.

Their book What Good Is Heaven was published in September by Texas Review Press as part of its Southern Poetry Breakthrough Series. The publisher chose Hendrix to represent their home state of Alabama in the series, which highlights a first collection by poets in each southern state.

The invitation to be a visiting artist came as a surprise email to Hendrix. “It feels really validating as a writer, especially when I still feel so new to this in so many ways,” they said. Hendrix will be reading from What Good Is Heaven in Knoxville at a poetry night November 15 hosted by Union Avenue Books and including fellow English department faculty members Amber Albritton and Bess Cooley. Read one of the poems from their book online here.

Storyteller Tradition

Growing up in the Deep South influenced Hendrix’s interest in poetry.

“Southerners are natural storytellers, and so much of that storytelling is done orally,” they said. “I think that ties back into a much longer tradition of poetry, verse, lyrics—all that rhyme and meter and sound that’s meant to help you remember a story without need of writing it down.”

With a grandmother who taught English and a grandfather who was a journalist, Hendrix was always surrounded by stories. “Fiction is great, but I love the poem’s potentiality, its kinetic energy—it feels like tapping into something ancient and immortal and always alive, the way it moves and changes all the time,” they said. “There’s a wildness to poetry, even in the tightest forms. It’s fascinating, and I love being part of that tradition.”

Hendrix, whose poetry won the 2019 Keene Prize for Literature and Southern Indiana Review’s Patricia Aakhus Award, didn’t set out to write a book.

“I give myself permission to write a lot—and I mean a lot—of really, really bad poems that I know I’ll never even attempt to publish,” they explained. “I like to think of those poems as practice, or getting something out of my system—they often make the poems that come next sharper, more focused.”

“I started out just writing poems about what I knew: my childhood in rural north Alabama, animals, the mountains, farming, religion, queerness,” they said. “I started noticing that all these poems had similar themes, settings, and conceits, and at that point I did start to write towards a collection. It took several rounds of revision, though, before these poems had a clear arc that felt like a book.”

The collection that resulted is an extended meditation on mercy, they said, what it means, how it changes, how it can be violent, and how violence can actually be kindness, though not always. “It’s a queer coming-of-age narrative in a very restrictive place, but it’s also about how one becomes implicated in inflicting pain too, even with good intentions,” Hendrix said. “It’s also about finding love, finding the self, beyond that violence. I hope readers will experience that journey with openness, and come away from this book thinking about their own enactments of mercy.”

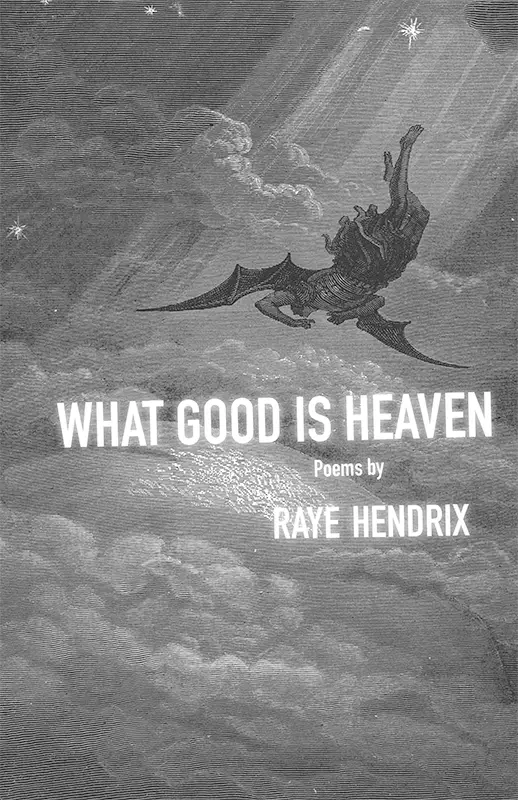

Because of the book’s title and some of the content, people sometimes assume that Hendrix is anti-religion. “I’m not at all,” they explained. “But I really do like to question what I’m told, so a lot of this book is questioning that kind of religion—the very specific regional Christianity I grew up around. ”The book’s cover image is of Lucifer from the illustrated Paradise Lost, a choice that Hendrix said also can be misunderstood. “I love reading—or perhaps more accurately, intentionally misreading—Milton’s version of Lucifer as a sympathetic character. There’s something in Lucifer that I think is so beautifully, tragically human, and that kind of humanity is so central to my book. Flawed love, flawed mercy, are the imperfectly beating heart of it.”

Poetry and Disability Studies

Hendrix also completed their doctoral dissertation this year, combining passions for poetry and disability studies by delving into the poetics of imperceptible disabilities. They looked at questions such as how the mind, or asthma, or deafness shape a poem. “I felt that contemporary US poetry was a fruitful space for that kind of inquiry and analysis, since we’re seeing a sort of neo-confessionalism right now—poems that are very concerned with identity and representation,” they said.

An essay Hendrix wrote on Ilya Kaminsky’s poetry collection Deaf Republic has been accepted for publication by PMLA, the journal of the Modern Language Association of America.

Hendrix’s book of poetry received a 2024 Weatherford Award, which honors books deemed as best illuminating the challenges, personalities, and unique qualities of the Appalachian South.

By Amy Beth Miller