Good Research Neighbors: Measuring Innovation in Urban Areas

A UT research center team published a new study in npj Complexity that challenges conventional wisdom on how city size fuels innovation.

Researchers with UT’s Center for the Dynamics of Social Complexity (DySoC) published a new study in npj Complexity revealing that the method by which cities are measured—and not just their size—profoundly shapes patterns of innovation and inequality.

Anthropology Professor and DySoC Director Alex Bentley coauthored the study with external DySoC members Sergi Valverde, of the Spanish National Research Council, Barcelona, and Blai Vidiella, of France’s Centre National de Recherche Scientifique; and lead author Salva Duran-Nebreda, of Institute of Evolutionary Biology in Barcelona.

The team found that spatial clustering and ranges of cooperation matter as much as population size when it comes to patents and technological creativity in US cities.

“While the ‘scaling law’ between innovation and population size has long been known, this study shows for the first time that it is not one-size-fits-all,” said Bentley. “Scaling outcomes change depending on how much space around a location is considered.”

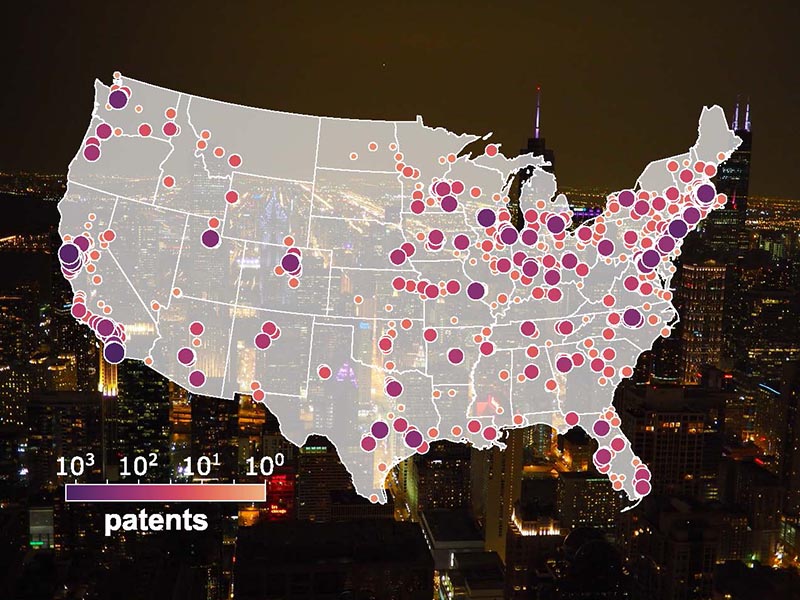

Their study, Fractal clusters and urban scaling shape spatial inequality in US patenting, analyzed US patent data at different radial distances around urban centers. They found that scaling between population and innovation intensifies up to around 20 kilometers, then dissolves. Beyond this “commuting distance,” simply adding more people doesn’t translate into more effective interactions.

“The findings highlight two main variables for policy,” said Valverde. “Innovation depends on both intensity—how productive local clusters are—and participation—how many different places contribute. Previous models collapsed these effects into a single scaling exponent, which helps explain why past studies often reported inconsistent results.”

Within compact urban core areas (from 3–4 kilometers), innovation inequality is stable. Superlinear scaling—the idea that “bigger is better”—emerges not by endlessly enlarging one core but by connecting multiple cores within around 20 kilometers. Beyond 20 kilometers, extra population does not equal more effective interaction, setting a natural boundary on forecasts that assume unlimited innovation growth from larger populations.

“For public policy, the study suggests that boosting innovation is not simply a matter of adding population to metropolitan areas,” said Bentley. “Instead, investments should focus on connectivity within approximately 20 kilometers, where there is better transit, dense meeting places, campus clustering, and cross-core bridges.”

Policymakers should also recognize the trade-off between population intensity and wider geographic inclusion: broadening participation may lower per-capita intensity, but it engages more communities. For researchers, the results underscore the need for multiscale diagnostics such as coefficients of variation at different distances, rather than relying on single-number scaling laws.

“Urban scaling is not just about population size but also about the spatial organization of people and inventors,” said Valverde. “While population is essential for innovation, its payoff is limited by the geometry of how people cluster and interact.”

By Randall Brown